Digging a Hole Through Earth

Where in the world would you end up if you dug in a certain direction?

- 🎓 Part of my thesis on Interactive Data Physicalizations

Context

For thousands of years, physical objects have been used to represent data – like using pebbles to account for votes in ancient Greece. Such representations, especially newly computer-supported ones, became the focus of an emerging field called data physicalization.

As part of my master’s in interaction design, I explored how data physicalization and tangible interaction could be combined. More specifically, I studied how an object might convey data not through its shape, but only through our interaction with it.

I proposed a tangible and embodied artifact (a shovel equipped with orientation sensors) that could be used by visitors of Earth sciences museums.

By pointing the shovel to the ground at different angles, visitors could learn where in the world they would end up, if they were to dig a hole towards that direction.

In order to perform such calculation, I created SuperTunnel Simulator – an application that would be running in an electronic device attached to the shovel.

Don’t you have a shovel at hand?

Don’t worry! You can check a standalone version of the simulation at supertunnel.app, which runs on both desktop and mobile devices.

Process

Well, that shovel idea didn’t come out of thin air.

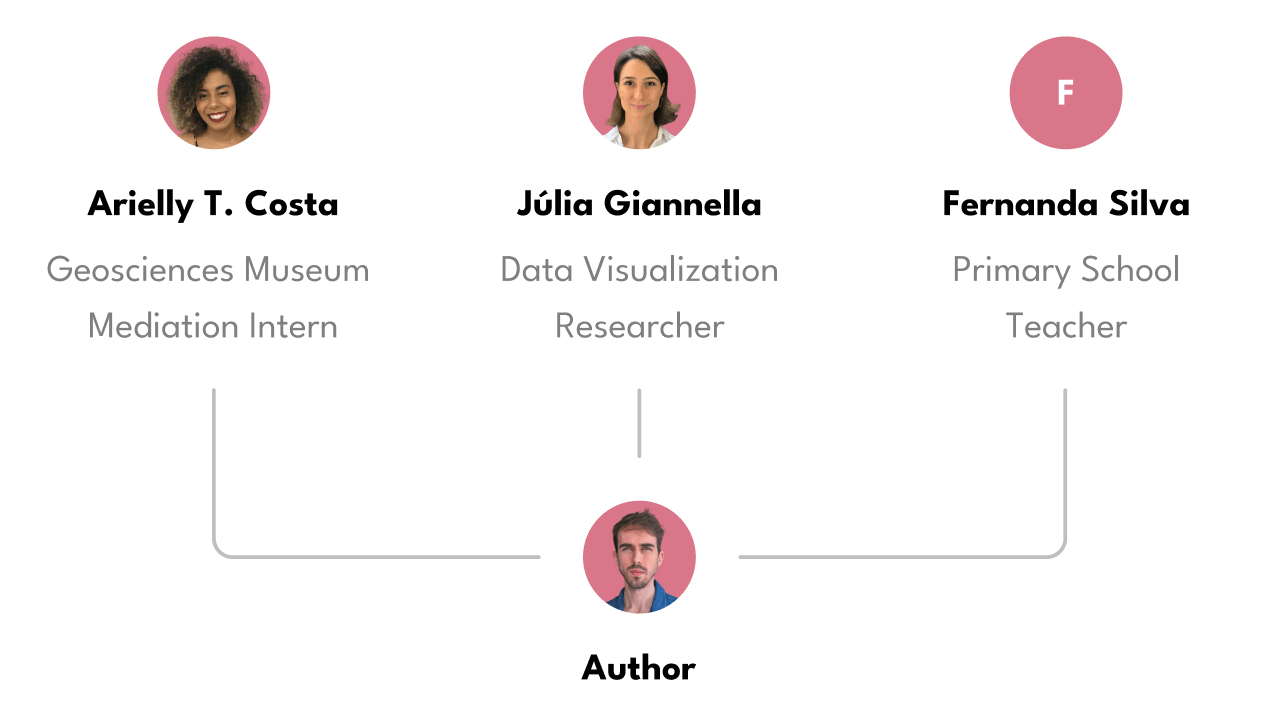

In order to ideate based on a concrete use situation, I focused on museum visitors – more specifically, visitors of the Geosciences Museum of University of São Paulo.

Besides interviewing museum staff, I have also talked to researchers and practitioners of related areas – as depicted in the diagram below:

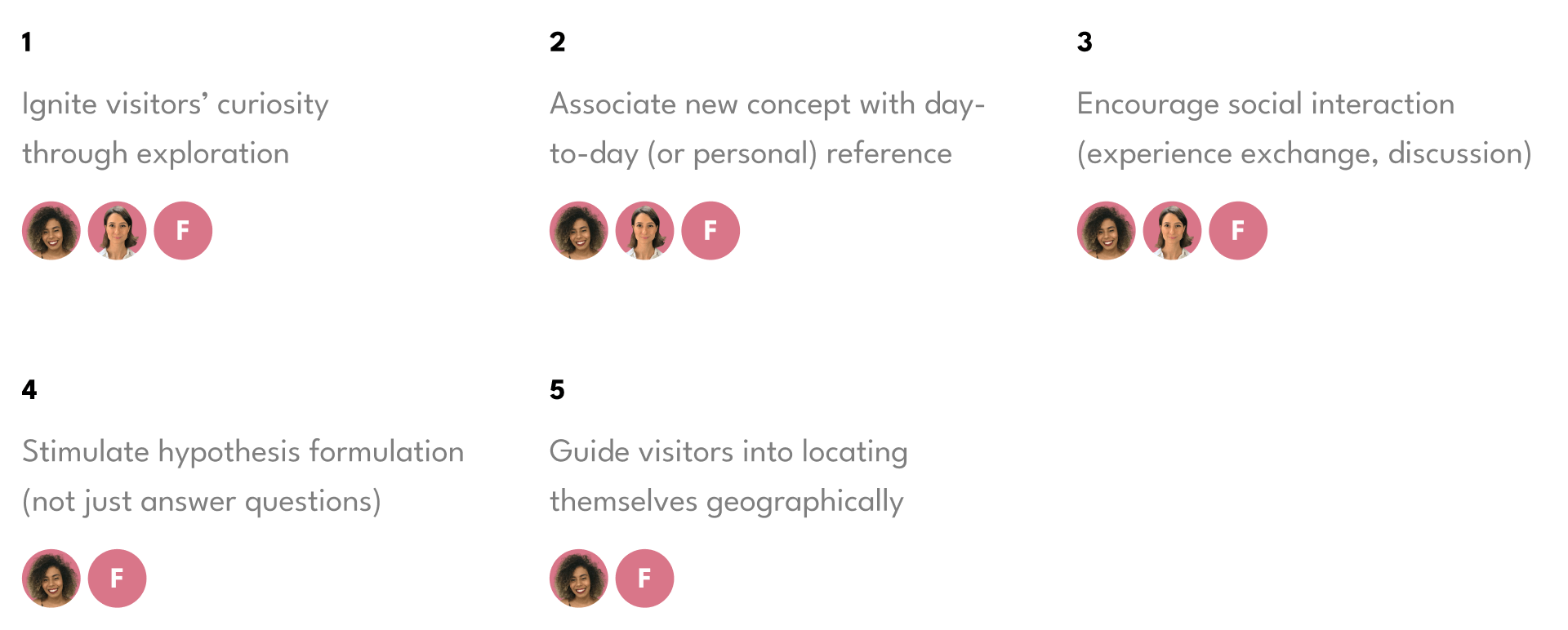

The interviews were truly insightful – and I condensed them into 5 guidelines for my project – which were phrased as the following pedagogic principles:

- Ignite visitors’ curiosity through exploration.

- Associate new concept with day-to-day (or personal) reference.

- Encourage social interaction (experience exchange, discussion).

- Stimulate hypothesis formulation (not just answer questions).

- Guide visitors into locating themselves geographically.

After generating dozens of project ideas that could address the above guidelines, the “magic shovel” idea sounded the most promising.

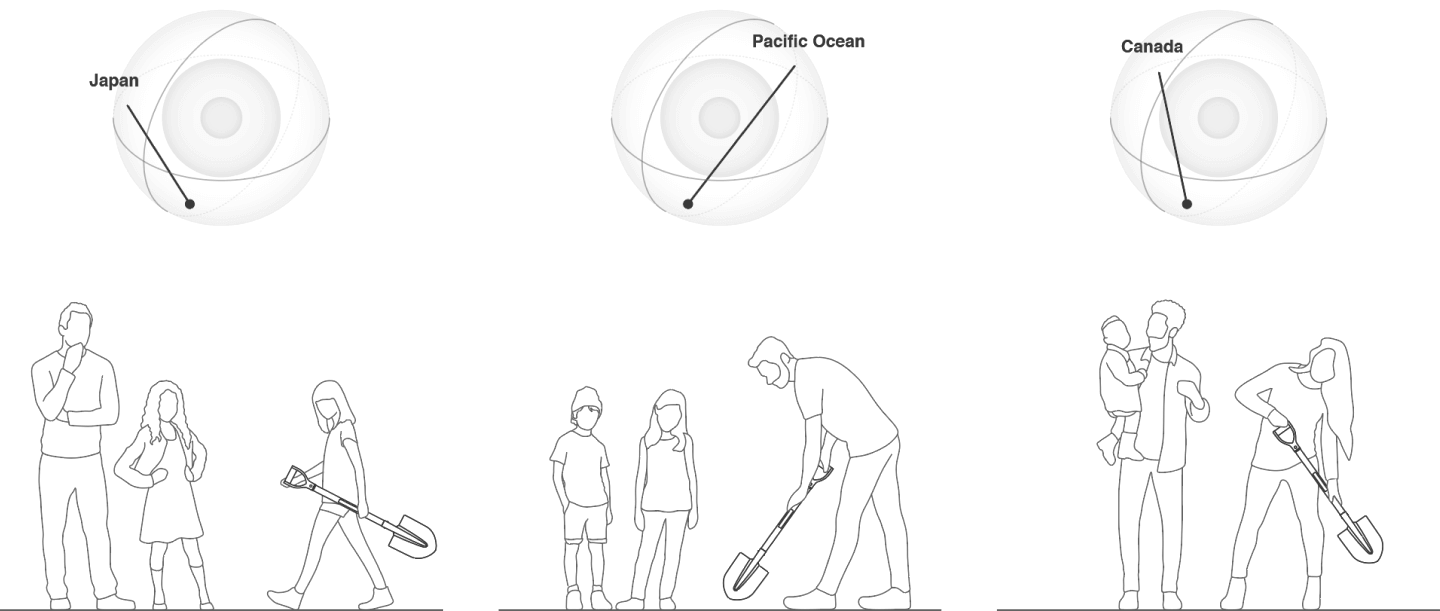

In order to better communicate it, I illustrated different people using the shovel, as well as a visual representation of the simulated tunnel on a globe:

Feedback on that idea was mostly positive, so I moved on to creating a working prototype. The first approach was to use an Arduino board attached to the shovel:

Despite the promising experiments with Arduino, I ran into some technical issues (like the orientation data not being precise enough). So I decided to create the next prototype using the built-in sensors of a smartphone.

After experimenting with an old iPhone, the orientation data seemed more realiable, North direction was easier to obtain and GPS was already built in. Now, I needed a way to attach the phone to the shovel:

Besides providing more accurate sensor readings, the phone’s screen was also beneficial, as a way to provide vistors with visual feedback.

By running supertunnel.app on the phone attached to the shovel, visitors could see (on the screen) their hypothetical destination be updated as they moved the shovel.

The following video represents a potential visitor (in this case, myself) playing with the shovel and simulating a tunnel from Brazil to China, Russia, Australia, India and many other countries.

Within the museum, there could be a projection of the 3D globe, animated in real time according to the shovel’s movement.

Finally, even though the protoype was not tested in a real museum scenario (due to the pandemic), early feedback from participants sounds promising.

Responses indicate such interaction might influence learning not by strictly teaching content — but by igniting visitors’ curiosity and stimulating hypothesis formulation.

In a broader sense, my thesis points to opportunities on investigating ways to convey data not through an objects’s shape, but only through our interaction with it.